Have you ever stood over a machine, listening to the metallic stutter of a cutter, and felt a peculiar mixture of guilt, dread, and shame, as if the tool were judging you?

The 2026 Guide To Eliminating Chatter, Deflection, And Vibration in CNC Machining

You’ll find this guide conversational, slightly opinionated, and full of practical steps you can test on the shop floor tonight. It’s written for the person who runs the machine, the CAM programmer who sleeps beside a stack of tool holders, and the engineer who prefers graphs to people — but still likes people.

Why you should care about chatter, deflection, and vibration

You care because these three nuisances cost you money, time, and credibility. They make parts out of tolerance, shorten tool life, harm surface finishes, and generate scrap — or worse, a call from quality that begins with, “We need to talk.” Beyond lost parts, persistent vibration is a sign your process isn’t behaving predictably, which undermines scalability and productivity.

Definitions: chatter, deflection, and vibration

You need clear terms to act. Without clarity, every complaint becomes “it vibrates,” and nothing improves.

- Chatter: Self-excited oscillation caused by regenerative effects between the tool and the workpiece. It creates harmonics you can often hear and sawtooth marks on the surface.

- Deflection: Static or quasi-static bending of the tool, toolholder, or workpiece under cutting forces, leading to dimensional error.

- Vibration: Any oscillatory motion in the system. Chatter is a type of vibration, but vibration can also be forced (from imbalance, misalignment) or transient.

Each of these can occur alone or together. Your job is to identify the dominant mechanism and respond accordingly.

How these problems show up: symptoms and initial checks

When you encounter a problem, paying attention to the symptom will save you hours of guessing. Read the symptom, then run the simple checks listed.

| Symptom | Likely cause(s) | First checks you should do |

|---|---|---|

| Loud tonal noise, regular marks | Chatter (regenerative) | Reduce depth of cut, change spindle speed, shorten tool stickout |

| Irregular wobble, low-frequency hum | Forced vibration (imbalance, spindle bearings) | Check balance, spindle runout, toolholder cleanliness |

| Systematic dimensional error | Deflection | Measure tool stickout, increase rigidity of holder/fixturing |

| Burnished or smeared finish | Excess heat due to rubbing (low engagement) | Check feedrate, tool sharpness, coolant, chip evacuation |

| Increasing amplitude over time | Process instability, wear | Check tool wear, machine condition, dynamic response |

Every symptom suggests a class of corrective actions. Start with the simplest checks before you invest in expensive diagnostics.

Quick rules of thumb you can use right away

You’ll like rules of thumb; they feel like cheating but work surprisingly often. Try these before deep analysis.

- Halve the radial depth of cut and double the feed per tooth — if vibration drops, you’re removing regenerative engagement.

- Shorten tool stickout: every 1×D of stickout increases bending risk exponentially.

- Replace the toolholder taper if it’s contaminated — a dirty taper will generate runout and vibration.

- Prefer high helix and more flutes for finishes; prefer fewer flutes for heavy roughing where chip space matters.

These aren’t silver bullets, but they’ll often get you back to work so you can breathe and think.

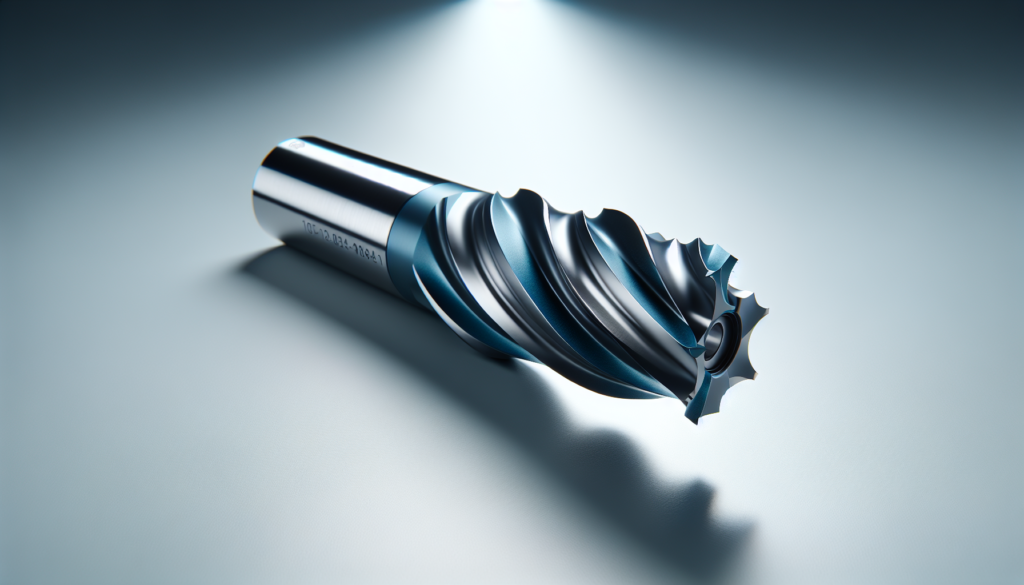

Tooling — selection and setup

Tooling is where the rubber meets the road. The right combination of cutter, holder, and stickout is your front-line defense.

Tool geometry choices

Tool geometry dictates stability and chip formation. When you select geometry, consider material, depth of cut, and finish requirement.

- Diameter: Larger diameters increase stiffness but require more power.

- Flutes: More flutes give better finish and allow higher feed per revolution but reduce chip clearance.

- Helix angle: High helix helps smooth cutting forces and chip evacuation but can increase axial force.

- Corner radius: Adds strength and can damp high-frequency vibrations.

Toolholder and taper considerations

A precise, clean taper is worth more than a dozen “optimizations” you’ll never do. You must treat toolholders as precision instruments.

- Use shrink-fit or hydraulic holders for best concentricity and clamping rigidity.

- Check taper cleanliness before mounting: a speck of debris can produce runout.

- Consider balanced holders for high-speed spindles; imbalance is a sure way to force vibration.

Stickout management

You don’t get to choose stickout after the part is revealed, but you can plan. Minimize stickout without creating collisions. Use extension reduction devices or modular tooling to maintain rigidity.

Fixturing and workholding

The workpiece is part of the dynamic system. A flexible part will sing under load, and not in a good way.

Principles of rigid workholding

You must clamp near the cutting zone when possible. Clamping should prevent movement in all axes, and you should support cantilevered features.

- Use dovetail or V-blocks for round bars to prevent rotation.

- Use step clamps and parallel supports for plates.

- Consider subplates, vacuum fixtures, or custom soft jaws for thin or complex components.

Damping within fixtures

You can add damping to fixtures via viscoelastic materials, tuned masses, or constrained layer damping. These reduce response amplitude without changing machining parameters drastically. Use them when part geometry prevents ideal clamping.

Process parameters: speeds, feeds, and depths

Parameter optimization is the simplest lever for mitigation. You will change RPM, feed, radial depth of cut (ae), and axial depth of cut (ap) more than anything else.

Speed and feed interactions

You can often cure chatter by changing spindle speed slightly. Stability lobe theory explains why — but you don’t need to be a mathematician to act.

- If you hear chatter, try a modest speed change of ±5–10% and monitor.

- Increase feed per tooth if surface finish is acceptable, as higher chip load can suppress rubbing.

- Use consistent chip thinning rules: with dynamic engagement, feed per tooth changes as step-over changes.

Depth of cut trade-offs

Lower radial depth reduces regenerative feedback; lower axial depth reduces overall force. For finish passes, use shallow ae and ap with higher spindle speed; for roughing, use large ap with reduced ae and trochoidal motion to maintain constant engagement.

Toolpaths and CAM strategies

Your CAM strategy can be as influential as your tooling. You’ll be amazed what a change from zig-zag to trochoidal milling can accomplish.

Modern toolpath types that reduce vibration

- Trochoidal machining: Keeps engagement constant and reduces instantaneous cutting forces.

- High-efficiency milling (HEM): Uses shallow radial engagement with high axial depth and high rpm; requires stiff setup and well-balanced toolholders.

- Adaptive clearing: Maintains consistent chip thickness and tool engagement, reducing force spikes.

When to use climb vs conventional milling

Climb milling generally produces better surface finishes and reduced tool wear. Use climb whenever chip evacuation and machine backlash permit. If backlash is present, conventional milling may be safer.

Damping devices and tuned solutions

Sometimes you need hardware. Passive damping and tuned absorbers can be lifesavers for specific setups like long boring bars.

Options for damping

- Tuned mass dampers: Add mass and damping to shift and reduce resonance.

- Viscoelastic liners: Cheap, reduce vibration at higher frequencies.

- Dynamic damped toolholders: Contain internal damping elements to suppress chatter.

Pros and cons table

| Device | Effectiveness | Cost | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuned mass damper | High for targeted frequency | Medium–High | Long boring bars |

| Viscoelastic liner | Moderate | Low | Fixtures, workholding |

| Damped toolholders | High | High | Finish operations at known speeds |

| Active damping systems | Very high | Very high | Production lines with recurring issues |

Choose devices based on frequency, cost, and repeatability. For one-off problems, cheap damping may be enough; for recurring volume work, invest in active or tuned solutions.

Diagnostics: how to measure and analyze

You’ll make decisions based on data when things get stubborn. Here’s what to measure and how.

Basic shop-floor diagnostics

Start with the human senses. Listen, look at chips, and examine surface finish.

- Are chips long and stringy or short and segmented?

- Is the noise tonal or broadband?

- Does the problem appear only at specific spindle speeds or always?

These observations narrow your search.

Instrumentation and analysis

When visual checks aren’t enough, use instruments:

- Accelerometers: Measure vibration amplitude and frequency directly. Place one on the spindle and one on the workpiece if possible.

- FFT analyzer: Converts time data to frequency domain to identify dominant frequencies.

- Laser vibrometer: Non-contact measurement for precise analysis.

- Spindle probe/runout tester: Measures concentricity and spindle health.

How to perform a simple impact test

An impact test helps reveal the system’s natural frequencies. Tap the toolholder with an instrumented hammer while recording accelerometer data. The peaks in the frequency response indicate resonant modes. If your cutting frequency hits these modes, you’ll chatter — and you can then choose a different speed or add damping.

Stability lobe diagrams: what they mean for your process

You don’t need to draw them from scratch, but understanding them helps you pick safe speeds.

- Stability lobes show which spindle speeds are stable for a given depth of cut.

- Peaks correspond to modal behavior; cutting within a lobe is stable for larger depths of cut.

- If you can access a stability lobes tool in CAM or analytic software, use it to pick a speed that maximizes material removal rate without crossing into instability.

Think of lobes like safe islands in a choppy sea. Aim for the islands.

Machine maintenance and tuning

If the machine is tired, you can’t expect perfect results. Regular maintenance keeps dynamics predictable.

Critical maintenance checks

- Spindle bearings: Listen for rumble and check temperature and backlash.

- Ball screws and linear guides: Grease them on schedule and check backlash.

- Toolchanger and turret: Ensure repeatability and secure clamping.

- Electrical and servo tuning: Poor tuning induces oscillation in axes.

Practical adjustment tips

- Check and clean the spindle taper after every tool change.

- Rebalance the spindle assembly if you add heavy tooling or adapters.

- Tighten loose components — even a small bolt can alter resonant behavior.

Material-specific strategies

Different workpiece materials behave differently under cutting. You must adapt.

Ferrous materials (steel, stainless)

Steel tends to generate higher cutting forces and work-hardening zones. Use lower cutting speeds for stainless, increased coolant, and sharp tools to reduce rubbing.

- Use tougher tool grades (e.g., PVD or multilayer coatings).

- Prefer smaller axial steps with more passes for finishes.

Non-ferrous materials (aluminum, copper)

These like high speeds and sharp edges. Aluminum is notorious for chip-welding and smearing, which can mimic vibration. Use high-helix, polished tools and ensure chip evacuation.

- Increase feed per tooth to prevent rubbing.

- Use coolant or mist to prevent built-up edge.

Composites and exotic materials

Composites have abrasive fibers and delamination concerns. Use specialized tooling, high spindle speeds, and reduced engagement strategies like “peeling” cuts.

Case studies: practical fixes that work

You’ll appreciate concrete examples. Here are three distilled case studies.

Case 1: The screaming endmill

Symptom: Loud tonal vibration at a certain spindle speed during finishing on stainless. Fix: Performed a simple speed sweep and found a stable lobe 8% higher. A slight RPM increase moved the process into a stable region and eliminated chatter without changing tooling. Lesson: Sometimes the best fix is a 10% change.

Case 2: The sagging wall

Symptom: Thin-walled part bent out of tolerance. Fix: Redesigned fixturing with added backing support and changed to trochoidal roughing to keep cutting forces low. Lesson: Fixturing and toolpath together beat mindless parameter tinkering.

Case 3: The old spindle

Symptom: Broadband vibration irrespective of cutting parameters. Fix: Instrumented with accelerometer, identified bearing resonance; replaced spindle bearings and rebalanced the assembly. Lesson: If the machine source dominates, no amount of CAM or tooling will help.

A troubleshooting checklist you can follow now

When a new problem appears, follow this checklist. It’s sequential, so do the earlier items first.

- Listen and observe: tone, chips, finish.

- Check tool wear and sharpness.

- Clean and reseat the toolholder; check taper and runout.

- Shorten stickout if possible.

- Reduce radial depth of cut by 50% and observe.

- Change spindle speed by ±5–10% and observe.

- Switch to conservative finish pass with reduced engagement.

- Add damping (viscoelastic, mass) to fixture or holder.

- Instrument with accelerometer and perform FFT if problem persists.

- Consider machine maintenance: spindle, guides, balancers.

These steps will solve the majority of issues without expensive interventions.

Economics: when to fix vs when to replace

You’ll need to balance the cost of fixes against throughput gains and scrap reduction. Ask these questions:

- Is this a one-off or recurring issue?

- Will a £500 damping device solve it permanently?

- Will new tooling or a CAM strategy pay for itself in X months?

- Is the machine under warranty or due for a rebuild?

If you face repeated problems on the same machine, replacement or major service often becomes cheaper than ongoing fiddling.

Tools and software recommendations for 2026

You’ll want the right digital tools as much as the right hardware. Here are types of tools that will help.

- Stability lobe and chatter prediction modules in your CAM package.

- Real-time monitoring software connected to accelerometers and the spindle.

- Simulation tools that include machine dynamics and tool deflection.

- Cloud-based repositories for process recipes and historical vibration data.

Adopt tools that integrate with your workflow, not ones that require a new religion to learn.

Final checklist for preventing vibration problems in production

Consistency is your ally. Preventive measures reduce the chance of crisis.

- Keep a clean taper and balanced holders.

- Standardize tool stickout and holder types across jobs where possible.

- Use adaptive toolpaths and trochoidal strategies for heavy cuts.

- Maintain a log of cutting speeds that produced chatter and the stable speeds you used instead.

- Periodically instrument and assess each machine to catch degraded dynamics early.

If you follow this, problems become rarer and more predictable.

Closing thoughts with a personal note

You will probably find that eliminating chatter is part experiment, part art, part maintenance. Like any good relationship, it requires attention, honesty, and occasionally the courage to admit you were wrong and buy a better holder. When you finally quiet a noisy process, you’ll feel oddly triumphant — a small, domestic victory over the laws of physics.

If you ever feel lost, remember: most problems are solved by tightening, cleaning, or moving a dial a little to the left. When those fail, instrument the system and give the machine a stern talking-to. It won’t listen, of course, but you’ll feel better.