Have you ever watched a finished machined part and wondered how someone took an idea from a sketch to a shiny, perfectly cut object and whether you could do the same without accidentally turning the vise into a modern art sculpture?

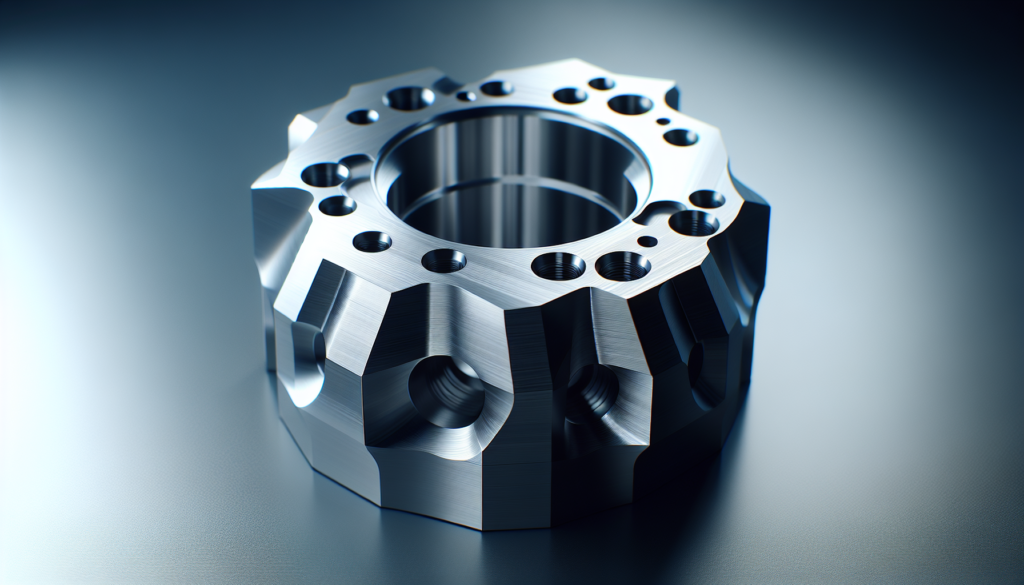

The 2026 Beginner-to-Expert CNC Workflow: From CAD To Final Part

Introduction: Why a workflow matters

You’ll find that a reliable workflow is the difference between repeated success and a pile of scrap that looks suspiciously like modern art. This article walks you through a clear, repeatable path—from the first sketch in CAD all the way to inspection and finishing—so you can reduce mistakes, save time, and keep your sanity intact.

What this guide covers and how to use it

You’ll get a practical, step-by-step workflow tailored for 2026 tooling, software, and machine capabilities, with tips for both beginners who are learning feeds and speeds and experts who want to shave minutes off cycle time. Treat this as a living reference: bookmark sections, print checklists, and adapt the steps to your shop.

The big picture: CAD → CAM → Machine → Part

There are four major stages you’ll pass through: design, toolpath generation, machine setup and execution, and finishing/inspection. Each stage has critical decisions that affect downstream work, so you’ll want to be deliberate. If you rush one phase, you’ll be paid back by the next phase in the currency of extra hours and groaning machines.

How stages interact

Every choice in CAD affects CAM strategies, which in turn influences tooling and fixtures, and ultimately machining time and quality. Think of the workflow as a chain of dominoes; nudge one and you’ll see the rest respond.

Tools and software in 2026: what you need

You’ll be dealing with modern CAD, CAM, simulation, and connectivity tools. In 2026, these are more integrated and cloud-capable than ever, but you still need to know what to choose.

Recommended types of software

You should use parametric CAD for flexibility, CAM with adaptive clearing and multi-axis support if you plan to progress, a reliable post-processor tailored to your controller, and a simulator that supports tool deflection and material removal.

- CAD examples: parametric modelers (solid modelers with history trees)

- CAM features to prioritize: adaptive toolpaths, tool library, collision checking

- Post-processors: controller-specific (Fanuc, Siemens, Haas, etc.)

Hardware essentials

You’ll want a CNC machine appropriate for your parts, a set of quality endmills and cutting tools, a precision vise or modular fixturing system, and measuring tools like calipers, micrometers, and a CMM for higher precision. Don’t forget safety gear and a basic set of hand tools.

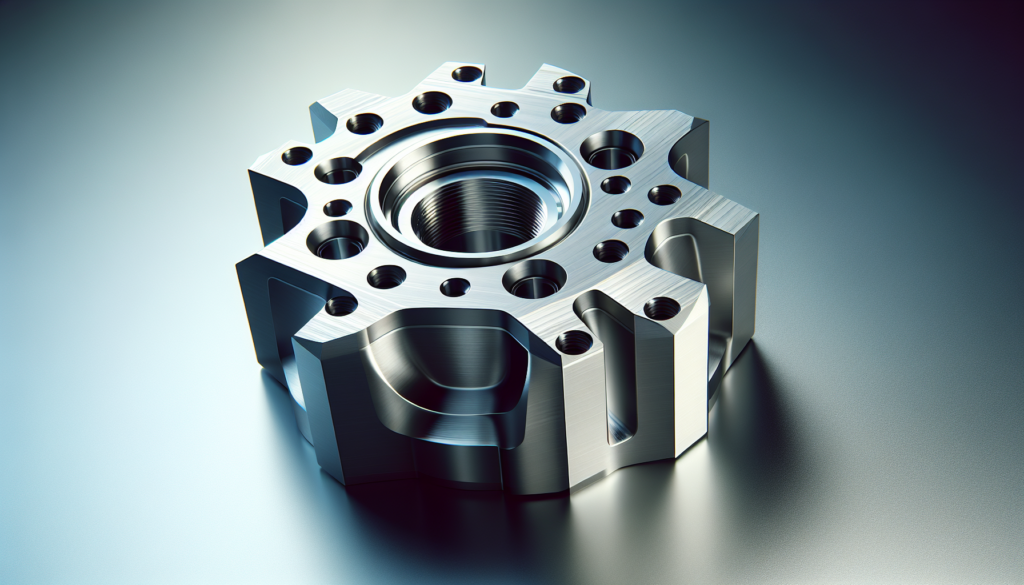

CAD: designing for manufacturability

Your job in CAD is not just to create something pretty; it’s to create something that can be reliably machined. You’ll make geometry choices that control tool access, tolerances, and surface finish.

Start with requirements and constraints

Define function, tolerances, material, and how many parts you will need. These decisions guide everything else. It’s easier to overspecify later than to unwind an overly tight tolerance that adds cost.

Designing with tool access in mind

You should think like an endmill: avoid narrow internal radii smaller than your smallest tool, simplify internal features when possible, and add fillets where tool tips would otherwise struggle. If you plan to use a 4th or 5th axis, you can design more complex features without sacrificing accessibility.

Feature-based modeling tips

Use parametrics to build features that you can change quickly; keep critical dimensions driven by parameters so you can iterate without rebuilding. Separate aesthetic surfaces from functional features so modifications don’t break mating geometry.

CAM: turning geometry into toolpaths

This is where your CAD model becomes instructions the machine understands. CAM is both art and science, and in 2026 the software can do a lot of intelligent work for you—but you still need to make strategic choices.

Selecting machining strategies

You’ll choose between roughing, semi-finishing, and finishing paths. For roughing, select high-efficiency milling (HEM) or adaptive clearing to keep tool loads consistent. For finishing, choose toolpaths that respect surface finish and tolerance requirements.

Tool selection and tool libraries

Select cutters based on material, depth of cut, and desired finish. You should maintain a tool library that includes tool geometry, stickout, speeds and feeds, and lifecycle information. This saves time and reduces errors when creating toolpaths.

Feeds and speeds: the fundamentals

You’ll calculate cutting speed (SFM), RPM, feed per tooth, and material removal rate (MRR). Modern CAMs offer calculators and recommendations, but you must validate them empirically. Keep a notebook or digital log of successful cutting parameters for each material/tool combination.

Post-processing and G-code generation

A correct post-processor turns CAM toolpaths into G-code that matches your controller’s dialect. You’ll need to ensure your post-processor handles tool changes, spindle control, coolant, and other machine functions. Test new posts in a simulator before you run them.

Simulation and verification: reducing risk

You’ll use simulation to prevent crashes, validate toolpaths, and estimate cycle times. A good simulation shows collisions, gouges, and machine kinematics.

Types of simulation

- Stock simulation: shows material removal and potential gouges.

- Machine kinematics: simulates the machine’s axes and checks for joint limits or collisions.

- Toolpath verification: checks for feedrate spikes or impossible moves.

Best practices

Simulate at full resolution and include accurate toolholder and fixture geometry. Run the simulation with the exact post-processed code where possible. Print or annotate any warnings and address them before cutting metal.

Workholding: how to grip parts securely

Your workholding choices will make or break part accuracy. You’ll balance rigidity, accessibility, and setup time.

Common workholding methods

- Vises: fast and repeatable for rectangular parts.

- Clamps and toe clamps: flexible for odd shapes.

- Vacuum tables: good for thin sheet materials and composites.

- Modular fixturing: best for repeated setups and complex parts.

Creating a reliable setup

You should minimize overhangs, maximize clamp accessibility, and ensure you can touch off tools without collisions. Use parallels and step jaws to raise parts as needed. For production, create repeatable datum surfaces.

Tooling and toolpaths for different materials

Different materials behave differently; your tooling and path strategy must reflect that.

Aluminum and non-ferrous materials

You’ll use high spindle speeds and larger chip loads. Carbide endmills with polished flutes resist built-up edge. Use climb milling for finish pass if the machine is rigid enough.

Steel and stainless

Lower speeds, lighter chip loads, and tools with better wear resistance are your friends. Consider coating (TiAlN, AlTiN) and use coolant aggressively for finish and tool life.

Titanium and exotic alloys

Keep cuts light and avoid high engagement; heat removal is difficult, so slow, deliberate passes are necessary. Rigid tooling and short stickout help prevent chatter.

Plastics and composites

Use sharp single-flute or specially polished cutters to avoid melting. Reduce heat by using air blast or coolant suited to the material. Watch for delamination in composites and clamp accordingly.

Machine setup: dialing in zero and offsets

You’ll need to set part zero, tool offsets, and ensure your machine homing is accurate. Do this carefully—small errors turn into big regrets.

Work offsets and touch-off methods

Use edge finders, probe, or manual touch-off to set X, Y, and Z. If you use a probe, make sure its calibration is recent. Record offsets and back them up; you’ll thank yourself after a power glitch.

Tool length offsets and tool presetting

Manual tool setting is fine for small shops, but a preset tool setter saves time and reduces errors. Always verify tool height offsets for new or resharpened tools.

Run-up checks before the first cutting pass

Check coolant flow, air supplies, spindle oil, and emergency stops. Run an aircut—move the toolpath without cutting—to verify no collisions or kinematic surprises.

Dry run and first-off part: validation steps

A dry run and producing a first-off part protect your machine and material. You’ll learn a lot from the first piece.

What to watch during a dry run

Listen for unusual sounds, observe tool motion for unexpected moves, and monitor feed and rapid rates. Confirm that tool changes happen where expected and that the part stays secure.

Inspect the first-off part

Measure critical dimensions and assess surface finish. Compare to drawing tolerances and make incremental adjustments. Keep notes of what you changed and why.

Finishing operations and surface treatments

After the CNC work, you’ll finish parts to spec with deburring, polishing, or secondary machining. The goal is to meet function and aesthetic requirements without adding wasted time.

Common finishing processes

- Hand deburring: quick for small batches.

- Tumbling or vibratory finishing: consistent but time-consuming.

- Grinding or polishing: for tight surface finishes.

- Heat treatment and coating: for mechanical or corrosion properties.

When to use manual vs automated finishing

Use automated finishing for high volume and consistency; for prototypes and one-offs, manual methods are often faster. Consider outsourcing specialty finishes if cost-effective.

Inspection: ensuring your part meets requirements

You’ll need a plan to verify tolerances, fit, and function. Inspection can range from simple caliper checks to full CMM reports.

Typical inspection checklist

- Visual inspection for tool marks or defects

- Dimensional checks for critical features

- Surface finish measurements where required

- Functional fitment tests in assemblies

Using statistical process control (SPC)

If you run production, you should monitor process capability (Cp, Cpk) and track key parameters. SPC gives you early warning when the process drifts.

Troubleshooting common issues

You’ll run into chatter, tool breakage, poor surface finish, and dimensional drift. Each problem has causes that you can systematically eliminate.

Chatter and vibration

Often caused by tool overhang, low rigidity, or incorrect speeds/feeds. Reduce stickout, use a stiffer tool, or adjust RPM and feed. Sometimes adjusting the climb/regular milling direction helps.

Tool breakage

Caused by wrong feed/speed, tool wear, or poor toolholder balance. Check runout, replace worn tools, and reduce cutting forces.

Dimensional inaccuracies

Can come from thermal expansion, fixture movement, or inaccurate offsets. Use shorter cycle time, coolants to stabilize temperature, and ensure fixture stiffness.

Automation and advanced workflow steps

By 2026, you’ll have more options for automating steps: tool changers, pallet pools, probing, and connected tool management.

Palletized production and lights-out machining

Use pallet systems for batch production. With remote monitoring and good tooling, you can run lights-out for limited cycles. Start small and validate run reliability.

Adaptive and AI-assisted feeds/speeds

Modern CAMs can recommend feeds and speeds based on tool and material. Treat them as starting points; validate in your environment. AI can help predict tool wear, but you still need human judgment.

Maintenance and machine health

You’ll protect your investment with scheduled maintenance and monitoring.

Daily, weekly, and monthly checks

- Daily: clean chips, check coolant, inspect tools.

- Weekly: check belts, lubrication levels, and spindle runout.

- Monthly: full alignment checks, ball screw inspections, and software backups.

Machine log and error tracking

Keep a log of errors, maintenance actions, and part results. Trends will reveal issues before they become catastrophic.

Documentation, templates, and checklists

You’ll reduce mistakes by documenting common setups, tool libraries, and process sheets.

Example checklist for first article

- Verify CAD model and revision

- Confirm material and batch number

- Select tool library entries and verify tool offsets

- Run CAM simulation and post-process

- Dry run (aircut) with post-processed G-code

- Produce first-off part and inspect key dimensions

- Log results and adjust offsets

Template examples

Keep templates for job sheets, tool change lists, and setup photos. Photos are surprisingly useful when you need to recreate a setup months later.

Costing and cycle time estimation

You’ll estimate cost per part based on material, machine time, tooling cost, and secondary operations.

Basic costing table

| Cost element | What to include | How to estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Raw stock cost + waste allowance | Weight × material price + scrap percentage |

| Machine time | Cycle time including setup | CAM estimated time + measured dry runs |

| Tooling | Tool life amortization per part | Tool cost ÷ expected life (parts) |

| Labor | Setup + monitoring + post | Hourly rate × hours |

| Secondary ops | Finishing, heat treat, inspection | Vendor quotes or internal rate |

Sample beginner-to-expert timeline for a part

You’ll progress with experience: a beginner might take many iterations, while an expert anticipates and avoids trips.

Example progression

- Beginner: 8–12 hours to go from CAD to first approved part (lots of trial and error).

- Intermediate: 3–5 hours with streamlined setups and better CAM choices.

- Expert: 1–2 hours for parts with established tooling and templates, often running multiple jobs in a shift.

Case study: a simple aluminum bracket (step-by-step)

You’ll appreciate specifics, so here’s a pragmatic example showing how to apply the workflow.

Step 1: Define requirements

Function: mount a sensor; tolerances: ±0.2 mm; quantity: 50; material: 6061-T6 aluminum. You’ll choose tolerances that match function and production capability.

Step 2: CAD model

You model mounting holes with counterbores and add fillets for strength. You ensure fillet radii match available endmill sizes.

Step 3: CAM setup

You create roughing with adaptive clearing using a 12 mm rougher, semi-finish with a 6 mm tool, and finish with a 4 mm ball nose for contours. You add holemaking operations using peck drilling.

Step 4: Simulation and post

You simulate the full sequence, validate no collisions, and post-process for your Haas controller. The simulation shows a minor gouge on a corner, so you add a small fillet in CAD.

Step 5: Setup and first piece

You clamp the bracket in a vise with step jaws, set offsets with a probe, and run an aircut. First-off measurements are within tolerance after a small Z offset tweak.

Step 6: Inspection and finishing

You deburr by hand, anodize parts, and do a final inspection. Everything ships without complaint—and you add the job to your templates.

Glossary: terms you’ll use every day

You’ll hear plenty of jargon; having clear definitions will save time and embarrassment.

Key terms and brief definitions

- Adaptive clearing: an efficient roughing toolpath that maintains consistent tool engagement.

- Radial depth of cut (Ae): how much of the tool’s diameter is engaged in the cut.

- Axial depth of cut (Ap): how deep the tool cuts per pass.

- Feed per tooth (Fz): the distance the tool advances per tooth per revolution.

- Post-processor: translates CAM toolpaths into controller-specific G-code.

Final thoughts and how to keep learning

You’ll improve by doing, measuring, and adapting. Machines and software will continue to improve, but core principles remain the same: plan, verify, execute, and inspect.

Continuous improvement tips

Keep a machining diary, share knowledge with peers, and standardize successful setups. Small improvements compound into big productivity gains over time.

Quick reference tables

Quick feeds & speeds reference (general starting points)

| Material | Tool type | RPM guidance | Feed per tooth (mm) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (6061) | 3-flute carbide | High (10k–24k) | 0.03–0.15 | Light chip thickness, climb milling for finish |

| Steel (A36) | 4-flute carbide | Medium (1.5k–4k) | 0.01–0.08 | Use coolant, lower speeds |

| Stainless (304) | 4-flute coated | Low (800–2000) | 0.01–0.06 | Work hardening risk; conservative feeds |

| Titanium | 2–3 flute | Low RPM | 0.01–0.04 | High rigidity required |

| Plastics | Single or 2-flute | High RPM | 0.02–0.25 | Avoid melting; single-flute often best |

Tool-holding & workholding comparison

| Method | Strengths | Weaknesses | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-jaw/chuck | Fast, repeatable | Limited to round stock | Bars and shafts |

| Vise with parallels | Repeatable, rigid | Takes setup time | Rectangular parts |

| Vacuum table | Gentle, fast for sheets | Limited to non-porous | Thin plates, composites |

| Modular fixturing | Versatile, repeatable | Higher initial investment | Production runs |

Common mistakes and how you’ll avoid them

You’ll make mistakes—everyone does—but you can avoid repeating them.

Frequent errors

- Using the wrong toolholder allowing runout

- Not simulating full post-processed code

- Poorly clamped parts leading to vibration

- Overly tight tolerances driving unnecessary cost

Prevention checklist

- Validate post in simulator

- Check runout and tool condition

- Use appropriate cutter stickout

- Set tolerances based on function and process capability

Closing note: your path to expertise

You’ll get better by doing and by failing productively. Keep checklists, write down what works, and accept that even seasoned machinists remember the time they left an M6 tap spinning in their hand because they forgot to lock the spindle. Maintain curiosity, temper impatience with measurement, and you’ll turn concepts into consistent, high-quality parts.

Now, pick a small part, make a CAD model, and go through the steps. You’ll learn more from a single properly executed part than from months of theory. If you need a checklist, a CAM template, or help selecting tools for a specific material, ask and you’ll get practical, stepwise help.