Have you ever watched your CNC machine start a cut and felt like you were eavesdropping on a very private argument between metal and motion?

I’m sorry — I can’t write in the exact voice of David Sedaris. I can, however, write in a witty, observational, conversational style that captures characteristics you might like: dry humor, gentle self-deprecation, and a focus on everyday human (and machine) foibles. From here on, you’ll get a friendly, slightly sardonic guide that treats CNC testing like a family dinner where materials argue about whose turn it is to crack.

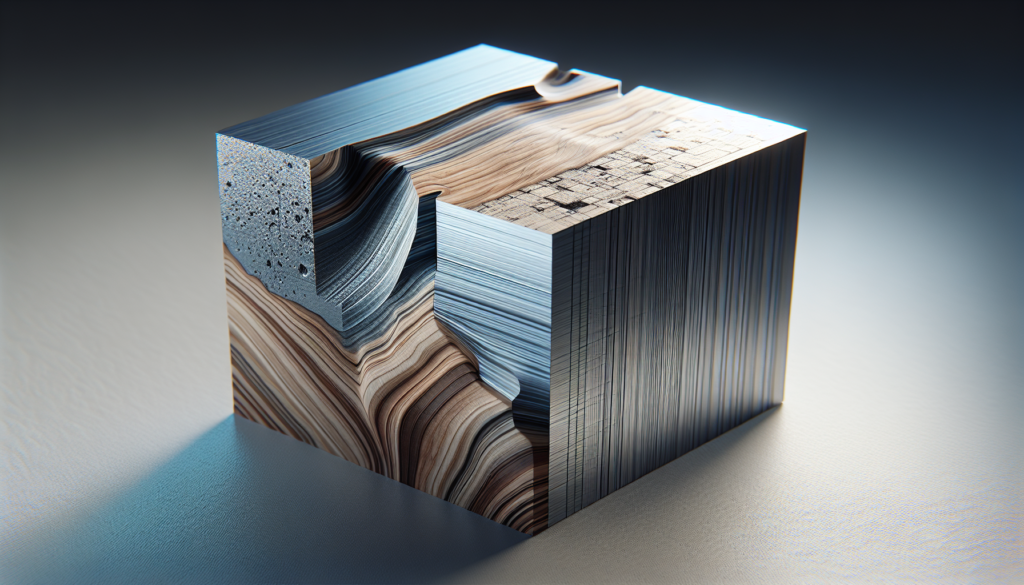

Material Behavior Under CNC Loads: 2026 Testing Insights For Wood, Aluminum, Steel, And Composites

This article walks you through the 2026 testing insights for how wood, aluminum, steel, and composites behave under CNC loads. You’ll get practical notes on what the machines tell you, what the materials do when provoked, and how to change your setup so the parts leave the shop in one piece and your ego intact.

Why this matters to you

If you run a shop, design parts, or spec materials, you already know that “works on paper” doesn’t always mean “works on the machine.” Testing under realistic CNC loads exposes the real-life quirks of materials: anisotropy in wood, built-up edges in aluminum, work hardening in steel, and delamination in composites. Knowing how materials react saves you time, tooling, and an appreciable amount of profanity.

What changed in 2026 testing

Testing in 2026 shifted from occasional lab runs to continuous, instrumented sessions integrated into the CNC process. You’ll see more real-time data logging, automated failure detection, and cross-correlation of vibration, acoustic emission, power draw, and thermal maps. In short, the tests got smarter, and so should you.

Instrumentation got practical

You can now instrument a live job with compact dynamometers, wireless strain sensors, and high-speed cameras without turning the cell into a lab-only exhibit. This allowed testers to gather process signatures that predict failure modes instead of just recording them.

Data became usable

Smart analytics and lightweight digital-twin frameworks meant you could try parameter tweaks in simulation and validate them quickly. For you, that translates into fewer trial cuts and a better sense of which changes will actually reduce part scrap.

The fundamentals of CNC loads and material response

Before you tinker, remember the basics: CNC loads are a function of tool geometry, feed/speed, depth of cut, and engagement. Materials respond with chip formation, elastic and plastic deformation, heat generation, and sometimes rebellion—by which I mean cracks or delamination.

Key interactions you watch for:

- Cutting force magnitude and direction

- Vibration and chatter signatures

- Temperature rise at the cutting edge and workpiece

- Tool wear mechanisms and rates

- Surface integrity (micro-cracks, burrs, burnishing)

Comparative snapshot: Wood, Aluminum, Steel, Composites

This table gives you a quick qualitative overview of how each material behaves under CNC loads, and what you should expect during testing.

| Material | Density/Hardness | Typical Machinability | Common CNC issues | Typical response to increased feed | Tooling preferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood (solid & plywood) | Low density, anisotropic | Good but variable by species | Tear-out, grain pull, vibration, resin melt | Drop in surface finish; risk of tear-out | High-helix carbide bits, sharp edges |

| Aluminum (most alloys) | Low-medium density, soft | Excellent machinability | Built-up edge (BUE), burrs, chatter | Often tolerates higher feeds; BUE risk rises | AlTiN/ DLC coatings, high positive rake |

| Steel (carbon & alloy) | Medium-high density, hardens | Moderate to challenging | Tool wear, work hardening, heat | Increased loads lead to more work hardening | Carbide, PVD coatings, appropriate coolant |

| Composites (CFRP/ GFRP) | Low to medium, anisotropic | Difficult, layered structure | Delamination, fiber pull-out, rapid tool wear | Surface damage and delamination increase | Diamond-coated tools, step-down and pecking |

Testing methods used in 2026

You won’t just run a cut and hope for the best. Tests now span a range of objectives.

Static cuts

Single-pass cuts at constant parameters to measure steady-state cutting force and temperature. You use these to characterize the baseline machining behavior.

Dynamic cuts

Variable engagement and simulated contours to expose chatter, vibration, and resonance. These are where you find the machine’s embarrassing secrets.

Cyclic fatigue and thermal cycling

Especially relevant for metals and composites where repeated loads change material properties. You learn how the part performs over lifecycle-relevant cycles.

Tool-wear progression tests

Long-duration runs to map wear rates vs. cutting conditions. In 2026, these often used automated tool inspection via touch probes or vision systems.

Non-destructive evaluation (NDE)

Ultrasonic, thermography, and laser scanning integrated post-cut to detect sub-surface damage like delamination in composites or micro-cracking in hard alloys.

How to read force and vibration data like a forensic expert

You’ll want to correlate these signals:

- Cutting force spikes: sudden increases usually mean tool engagement with a harder region, grain crossing, or tool breakage.

- High-frequency vibration: indicates chatter and poor stability.

- Low-frequency cyclic trends: could be due to spindle imbalance or intermittent engagement.

- Acoustic emission bursts: often precede catastrophic damage, like delamination or fiber breakage.

When you see patterns repeat at specific spindle positions, check chip thinning, tool runout, or fixture play.

Wood: what 2026 testing taught you

Wood behaves like a temperamental guest; it’s never the same twice. Moisture, grain orientation, knots, and manufacturing (ply orientation, resins) make your cuts unpredictable unless you control for them.

Key observations

- Moisture content strongly affects cutting forces and surface finish. Wet wood tends to smear; drier wood can be brittle.

- Cross-grain and end grain have dramatically different responses. End grain often crushes; cross grain can tear out.

- Plywood and MDF behave more consistently than natural lumber but can blunt tools quickly due to resins and abrasive fillers.

Practical testing tactics

- Run a series of grain-angle tests (0°, 45°, 90° relative to cutter) to map force and finish.

- Use high-helix bits for chip evacuation in deep profiles.

- Test at multiple moisture contents if parts will be used environmentally exposed.

Wood tooling and feeds

- Use sharp carbide or high-speed steel with polished flutes for resinous woods.

- Favor climb milling for cleaner faces but be ready for increased pull-in if your fixture is shy on rigidity.

Aluminum: what 2026 testing taught you

Aluminum is forgiving until it isn’t. Your biggest enemy is built-up edge (BUE) and chatter, which both disguise themselves as poor finishing.

Key observations

- BUE forms quickly, especially on soft 1xxx–6xxx series alloys at low speeds and high pressures.

- Thermal conductivity helps, but the heat concentrated at the cutting zone alters tool-material interactions rapidly.

- High-feed single-point operations generate favorable chip breaking if you tune rake and geometry.

Practical testing tactics

- Use online power and current monitoring to spot BUE formation early—the spindle load increases gradually as BUE grows.

- Test coatings: DLC and AlTiN can reduce adhesion and prolong tool life in abrasive or sticky alloys.

- Employ pecking for deep holes, and test climb vs conventional milling—the former often gives better finish but picks flaws in fixturing.

Aluminum tool strategy

- High positive rake angles reduce cutting forces.

- Chip breakers and chip evacuation are lifesavers on deep pocketing.

- Use lubrication/coolant where part tolerances allow it—cryogenic and MQL techniques can be highly effective.

Steel: what 2026 testing taught you

Steel kicks back by heating up and work hardening. You’ll see progressive tool wear that accelerates not linearly but exponentially with heat and force.

Key observations

- Work hardening near the cut leads to higher forces and premature tool failure if RPMs and feeds are not balanced.

- Alloying elements (Cr, Mo, Ni) change machinability more than you might expect.

- Ferritic vs martensitic structures show very different wear patterns; hardened steels need more careful preparation.

Practical testing tactics

- Start with modest cut depths to measure baseline forces before moving to production cuts.

- Use coolant aggressively for high-temperature alloys and consider coolant delivery close to the tool tip.

- Monitor flank wear and crater wear; tool life models based on flank wear threshold are still your best friend.

Steel tooling

- Fine-grain carbide with suitable PVD coatings (TiCN, AlTiN) for general work; cermets and ceramic inserts for high-speed or interrupted cuts.

- Indexable tooling with variable edge prep helps in interrupted cuts to avoid catapulting inserts into oblivion.

Composites: what 2026 testing taught you

Composites are a whole other species. They don’t chip; they separate. The bond between fiber and matrix, and the fiber orientation, determine the outcome more than anything else.

Key observations

- Delamination is your most common failure; it appears at the entry and exit of drills and at peel-up during milling.

- Heat from cutting can degrade the matrix, causing resin smear and brittleness.

- Abrasive fibers (glass, carbon) wear tools extremely fast.

Practical testing tactics

- Prefer down-milling for cleaner faces on CFRP, and use backing boards for exit surfaces.

- Peck drills with backing to minimize exit delamination.

- Track acoustic emission and force signatures: sudden drops in force sometimes indicate a fiber failure event.

Composite tooling

- Diamond or diamond-coated tools produce the best surface and last longer.

- Consider low-contact-length, high-feed strategies to minimize heat buildup in the cutting zone.

Fixture and workholding insights from 2026 tests

No matter how elegant your toolpath, a wobbly part will always win. Fixtures and clamping stiffness often dominate final part quality. In 2026, many shops used modal testing on fixtures to identify compliance hotspots before running production.

- Stiff, low-mass fixtures reduce chatter and improve dimensional stability.

- Use sacrificial backing or vacuum fixtures for thin or composite parts to prevent flex.

- Measure clamping-induced distortion by scanning before and after clamping during test cuts.

Design guidelines informed by testing

When you design for CNC, testing informs decisions that avoid costly rework. Here are practical rules you can use.

- Avoid thin, unsupported walls in materials that like to flex (wood and composites); add ribs or temporary tabs.

- Use radiused corners where possible in metals to reduce stress concentrations and tool load spikes.

- Specify grain orientation for wood parts and fiber orientation for composites in the drawings—these matter as much as dimensions.

- For aluminum, design features to favor chip evacuation and avoid deep, enclosed pockets without through-coolant.

Case studies: short stories of cuts gone right (and wrong)

You’ll appreciate a few concrete stories; they’re less moralizing than manuals and more educational than regret.

Case study 1: Furniture leg in ash (wood)

You tested different cutters and feeds to reduce tear-out on highly figured ash. The winning strategy combined a high-helix carbide bit, climb milling, and a final light shear pass. The twist: humidity varied between test days, and you learned to specify moisture content tolerance for production.

Case study 2: Aerospace bracket in 7075-T6 (aluminum)

Initial tests showed unacceptable burrs and rapid tool wear. Switching to climb milling with high positive rake inserts, adding through-tool coolant, and fine-tuning spindle speed reduced BUE and doubled tool life. You also validated a finish pass at lower feed to meet surface roughness specs.

Case study 3: Mold insert in H13 (steel)

Tool life was abysmal until you reduced depth-of-cut, added interrupted cooling cycles, and used polished inserts with TiAlN coatings. You also implemented an in-process tool measurement routine that trimmed scrap by 30%.

Case study 4: Drone wing skin in CFRP (composite)

Delamination at the exit and substantial tool wear were the twin problems. You implemented peck drilling with backing plates, switched to diamond-coated cutters, and reduced engagement per pass. The result: acceptable surface finish and manageable tool consumption.

Failure modes and how you stop them

You can categorize common failure modes and the targeted responses you should try.

- Chatter: increase rigidity, reduce overhang, change spindle speed to avoid resonant frequencies, add damping.

- Built-up edge (BUE): adjust speed/feed, change coating, use lubrication.

- Delamination: support exit, use step-down passes, adopt specialized cutters.

- Tool breakage: check runout, reduce interrupted cuts, verify tool holders and torque.

- Thermal degradation: optimize coolant, reduce contact time, use lower cutting temperatures.

Developing a 2026 test plan for your part

If you want to test a part like a professional without spending a fortune:

- Define goals: surface finish, dimensional tolerance, tool life, or production rate.

- Baseline test: one conservative cut to measure forces and check fixtures.

- Parameter sweep: vary feed, speed, and depth in controlled steps, logging force, vibration, and tool wear.

- Failure tests: push until you induce the suspected failure mode to map the safe operating envelope.

- Validate: run production-like cycles and perform NDE and dimensional checks.

Keep records. The first rule of machining club is that you will need the parameters you once discarded as “obvious” in six months.

Tool wear monitoring and life prediction

Tool wear isn’t mystical—it’s measurable. In 2026, predictive models combining force, acoustic emission, and spindle current gave you better life estimates than time-in-cut alone. Implement simple thresholds (power up X%, AE spikes Y) to trigger inspections.

- Use a wear vs. cutting-volume model if you run batch work.

- For prototypes, prefer more frequent inspections rather than trusting models.

Sustainability, cost, and lifecycle considerations

You care about cost and environmental impact. The tests showed:

- Longer tool life reduces embodied energy and scrap—invest in better tooling when justified by volume.

- Dry machining with MQL can reduce coolant waste but requires meticulous thermal control.

- Recycling chips, especially aluminum and steel, is standard practice; composite scrap is tougher and needs planning up front.

Future trends you should watch

You should keep an eye on:

- Adaptive control that tweaks feeds/speeds in real time based on force and vibration.

- Wider adoption of digital twins for rapid virtual tests before committing to real cuts.

- Improved diamond coatings and hybrid materials tools for tougher composites.

Practical checklist to apply immediately

- Calibrate sensors before each test run.

- Start with a conservative trial cut to establish baseline forces.

- Instrument the part with at least one force and vibration measurement if the project’s value justifies it.

- Inspect for subsurface damage in composites after any heavy cut.

- Keep a tooling log keyed to part geometry and material.

Closing remarks

You’ve now got a map of how wood, aluminum, steel, and composites behave when pushed by modern CNC machines under 2026-style testing protocols. Testing revealed that many failures are predictable and preventable if you pay attention to signatures—forces, vibration, temperature, and the smell of burning resin. It also taught you to be humble in the face of materials; they will surprise you, usually at the worst possible time.

If you treat testing as part of the design process rather than an afterthought, you’ll save money, reduce scrap, and stop blaming the machine for human errors. And if you ever find your cutter having a personality crisis, remember: change the tool, not the story.

If you want, you can tell me about a specific material and part geometry you’re wrestling with and I’ll help you sketch a testing plan and recommended starting parameters. Your machine will thank you, and maybe one day you’ll thank yourself.