Have you ever watched a machine stitch a chair, weld a bridge girder, or lay a microchip pattern and felt like you were watching a magician — except the rabbit is a robot and the trick is safety?

Fabrication Intelligence And Safety: Designing For Control

This is where intelligence meets steel, silicon, and sweat. You’ll find that designing for control is part engineering, part psychology, and part stubborn insistence that nothing should surprise you on a shop floor.

Why this matters to you

When fabrication systems gain sensing, decision-making, and actuation, the balance of control shifts. You could be a designer, operator, manager, regulator, or just someone who cares whether a machine behaves predictably. Whatever your role, the stakes are both practical and moral: safety, product integrity, liability, and trust.

What is Fabrication Intelligence?

Fabrication Intelligence refers to the use of sensing, machine learning, planning, and automation to perform manufacturing tasks with minimal human intervention. Think of it as giving factories a nervous system and a spine.

Core components of Fabrication Intelligence

You’ll usually see three layers: perception (sensors), cognition (algorithms), and action (actuators). Each layer carries its own safety obligations and failure modes, and you need to treat them like siblings who share a bathroom — one mistake affects everyone.

Designing For Control: the central idea

Designing for control means deliberately shaping systems so that control — whether by humans, automated controllers, or a combination — is clear, recoverable, and auditable. You want predictable behavior, defined authority, and graceful degradation.

Control vs. autonomy

Autonomy sounds like freedom until your CNC mill takes its own initiative. You should decide where autonomy is helpful and where control must remain with a human. This isn’t about resisting progress; it’s about assigning responsibility.

Safety as a design constraint

Safety is not an add-on. It’s a primary constraint that changes design choices at every layer. If you act like safety can be retrofitted, you’re asking for surprises — and factories don’t do surprises politely.

Safety trade-offs you’ll encounter

You’ll balance speed, precision, cost, and redundancy. Often you must accept lower throughput to achieve provable safety. That’s not pessimism; it’s engineering realism.

Common failure modes in fabrication systems

Understanding how things fail helps you design to prevent those failures. You’ll want to catalog common issues and plan for them.

- Sensor drift and calibration loss

- Algorithmic misclassification or false confidence

- Actuator wear and unexpected dynamics

- Communication latency and network partitioning

- Human error or misuse

- Cyber intrusions and data corruption

Why human error matters

You might blame the machine, but humans program, maintain, and override systems. Designing interfaces that prevent predictable human mistakes reduces incidents more than a dozen new sensors.

Principles for Designing for Control

You don’t need a manifesto, but you do need principles. These guide both high-level architecture and the tiny interface knobs that operators touch.

1. Explicit authority boundaries

Define who or what can make which decisions and under which conditions. You don’t want both a robot and an operator trying to reposition the same welding torch simultaneously.

2. Human-in-the-loop and human-on-the-loop clarity

Decide when humans must approve actions (in-the-loop) or when they observe and can intervene (on-the-loop). Clear modes reduce confusion and speed up incident response.

3. Explainability and observability

Make system decisions transparent. You’ll need logs, explanations, and visualizations so you can answer “why did you do that?” without invoking metaphors or a séance.

4. Graceful degradation

When something fails, your system should reduce capability predictably instead of catastrophically. A machine that slowly slows is better than one that explosively reconfigures.

5. Fail-safe defaults

Set defaults to safe states. If communication fails, the robot should stop or move to a protective position, not continue as if nothing happened.

6. Redundancy and diversity

Use different sensing modalities and independent decision paths when safety-critical outcomes are at stake. Redundant systems fail less often and in less synchronized ways.

Architectural patterns for control

There are established patterns that you’ll find useful. Some are classics from control theory; some are borrowed from avionics and nuclear safety because those industries have good taste in caution.

Supervisory control

A higher-level controller gives goals while lower-level controllers manage dynamics. You’ll like this pattern because it separates strategy from execution.

Hybrid systems

Combine continuous control with discrete decision-making. Fabrication processes often require both: one for real-time motion, another for sequencing and logic.

Runtime assurance (monitoring + fallback)

A separate, simple monitor checks the primary controller’s actions and intervenes if anomalies occur. Think of it as a nanny that’s boring but effective.

Safety analysis methods you should use

There are mature methods that help you reason about hazards. Use them, document them, and read them aloud as if they were promises.

FMEA (Failure Modes and Effects Analysis)

Break down components, identify failure modes, and evaluate their effects. You’ll get a prioritized list for mitigation.

HAZOP (Hazard and Operability Study)

Use teams to systematically imagine deviations from design intent and their consequences. It’s the method that forces people to say the word “what if” in a non-awkward way.

STPA (System-Theoretic Process Analysis)

Looks at control structures and unsafe interactions rather than component failures. It’s more modern and often better for complex software-driven systems.

Formal methods

For high-assurance subsystems, use rigorous mathematical verification. It’s like proofreading code with an army of obsessive editors.

Standards and regulations that guide you

Standards give you language and legal expectations. You’ll find them both reassuring and annoyingly specific.

| Standard | Domain | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| IEC 61508 | Functional safety general | Baseline for safety lifecycle of electrical/ electronic/programmable systems |

| ISO 13849 | Machinery safety | Focus on control systems and performance levels for industrial machinery |

| ISO 26262 | Automotive functional safety | Useful patterns for safety-critical motion and control |

| ANSI/RIA R15.06 | Industrial robots | Safety requirements specific to robots and their cells |

| NIST SP 800 series | Cybersecurity for industrial control | Frameworks and controls for securing ICS/OT environments |

How to use standards

You don’t need to memorize every clause. Use standards as checklists and as persuasive documents when you negotiate safety investments with accounting.

Verification and validation strategies

Verification proves the system meets specifications; validation proves the system meets user needs. You’ll need both.

Unit and integration testing for controllers

Test controllers in simulation first, then on hardware-in-the-loop testbeds. Simulators save fingers and budgets.

Scenario-based testing

Create normal and edge-case scenarios, including network outages and sensor faults. You’ll find that machines can be very creative in their failures.

Continuous monitoring and validation in production

Validation doesn’t stop at deployment. Use monitoring, anomaly detection, and offline analysis to learn and harden systems continuously.

Human-machine interfaces (HMI)

The HMI is where your design meets fallible flesh. A good HMI reduces mistakes; a bad one creates them with flair.

Principles for HMI design

- Make modes visible and actions reversible where possible.

- Use clear feedback: auditory, haptic, and visual cues should reinforce the same message.

- Avoid modal ambiguity; operators should always know who has control.

Training and documentation

Design for how people actually behave, not how you wish they would. Provide concise, scenario-focused training and keep documentation accessible and truthful.

Cyber-physical security: intersection of safety and cybersecurity

A breach can turn a cautious system into a rogue one. Security isn’t an add-on; it’s a safety measure.

Threats you should consider

- Command injection and manipulation

- Sensor spoofing and replay attacks

- Denial of service causing loss of control

- Insider threats and misconfiguration

Security controls that support safety

- Network segregation and minimal exposed services

- Cryptographic authentication for control commands

- Integrity checks for firmware and configurations

- Watchdog monitors that detect anomalous behavior

Supply chain and lifecycle considerations

Systems evolve. Components get updated. You’ll need processes to handle changes safely.

Configuration management and change control

Track dependencies, perform risk assessments for updates, and maintain rollback plans. You’ll sleep better if you can undo an upgrade that behaves poorly.

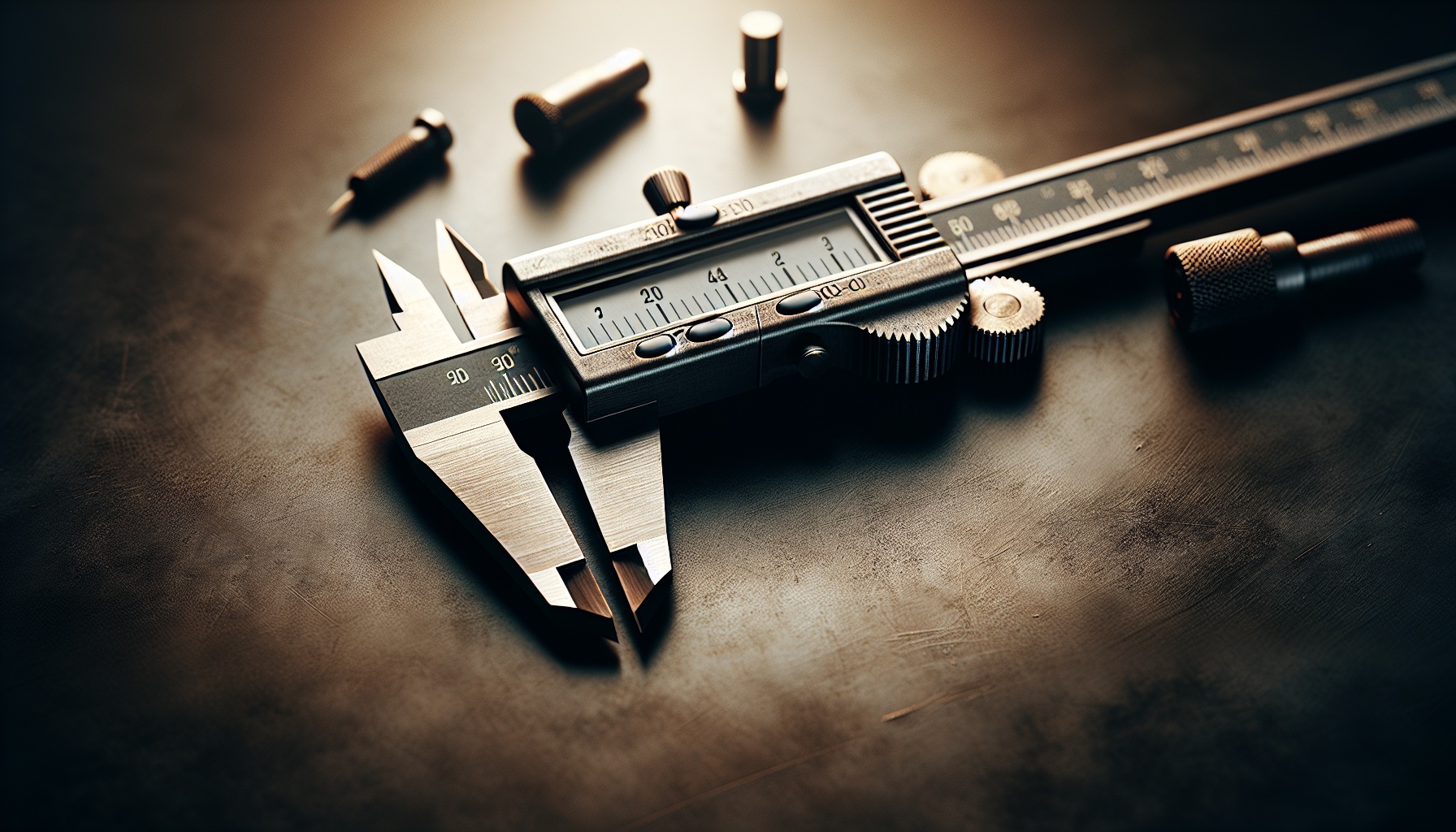

Maintenance and calibration

Schedule regular calibration and document procedures. Sensors that drift are small betrayals that cascade into big problems.

Organizational and cultural aspects

Technical fixes don’t last without cultural buy-in. You’ll want a culture that values near-misses as lessons rather than reasons for blame.

Roles and responsibilities

Define roles clearly: designers, operators, maintainers, safety engineers, and incident responders. Accountability reduces ambiguity in crises.

Incident reporting and learning systems

Encourage reporting by keeping it blame-free and focused on learning. Near-miss reports are gold — they’re warnings you can act on without tragedy.

Case study — a hypothetical press-fit line

Imagine you run a press-fit line for automotive assemblies. You introduce vision-guided robots to speed production.

What can go wrong

You might get misalignment due to a camera-LIDAR mismatch, an unmodeled tolerance causing jams, or an operator override that bypasses interlocks.

How to design for control

- Use dual sensing (camera + contact sensor) to confirm fit before applying full torque.

- Implement a supervisor that throttles force when variance increases.

- Keep a physical lockout that an operator must engage for manual intervention.

- Log every override and require a reason code for traceability.

Checklists you can use now

Here are practical lists you can use during design, commissioning, and operation.

Design-stage checklist

- Have you defined authority boundaries clearly?

- Is there a documented safety requirement specification?

- Have you selected standards and mapped requirements?

- Is there a runtime assurance layer planned?

- Are operator interfaces designed for clarity and reversibility?

Commissioning checklist

- Are sensors calibrated and verified on hardware?

- Have failure modes been injected in test runs?

- Is there a rollback and emergency stop procedure visible and tested?

- Are loggers and monitors operational and storing data securely?

Operational checklist

- Is daily health monitoring active?

- Are maintenance windows and calibration schedules adhered to?

- Are near-miss reports being reviewed and acted upon?

- Are software updates vetted via change control?

Metrics and KPIs for safety and control

You’ll want measurable signals to know whether your design works in practice.

| KPI | What it tells you | Target behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Near-miss rate | Frequency of close calls | Low and decreasing with proactive measures |

| Mean time to safe-stop | Response speed to critical faults | As short as practical for system dynamics |

| Override frequency | How often humans bypass safety | Low; each override should be justified |

| False-positive/false-negative rates (safety monitors) | Effectiveness of monitors | Balanced to avoid nuisance stops but catch real faults |

Using metrics responsibly

Metrics should guide behavior, not punish. Don’t create incentives to hide problems because that will destroy safety faster than a failed sensor.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

You’ll recognize these because they’re common and persistent.

- Treating safety as an afterthought. Fix: integrate safety from day one.

- Overrelying on a single sensing modality. Fix: add diversity and disagreeing checks.

- Building opaque models without fallback. Fix: combine ML with rule-based guards and monitors.

- Ignoring human workflows. Fix: co-design with operators and run pilots.

Emerging trends to watch

You won’t get a crystal ball, but you’ll get a useful horizon scan.

1. Safer ML models

Techniques like uncertainty estimation and interpretable architectures make ML safer for control decisions.

2. Digital twins and continuous validation

You’ll see more use of high-fidelity digital twins to test scenarios before they affect metal, which saves patience and parts.

3. Standardization of runtime assurance

Expect standards and best practices to converge on independent runtime monitor patterns for industrial AI.

Practical roadmap for implementation

If you want a step-by-step, here’s a pragmatic roadmap you can adapt.

- Define safety objectives and authority boundaries.

- Perform system-level hazard analysis (STPA/HAZOP).

- Architect primary and assurance controllers with clear modes.

- Design HMI and training programs with operator input.

- Implement simulation and hardware-in-the-loop tests.

- Commission with staged rollouts and monitored pilots.

- Maintain continuous monitoring, feedback loops, and culture of learning.

How to prioritize improvements

Start with what could cause the worst harm, then what’s easiest to fix, then what prevents repeated incidents. You’ll find quick wins build trust and credibility.

Budget and resource considerations

Safety costs money; poor safety costs more. You’ll need to justify investments with risk analysis and scenarios.

Cost-benefit approach

Quantify both tangible and intangible costs: downtime, recalls, reputation, and legal exposure. Use scenario probabilities and expected losses to build a business case; your CFO will be grateful for math.

Final recommendations — things you can do tomorrow

You can start making safer systems with minimal disruption.

- Run one STPA session with cross-disciplinary participants.

- Add a simple runtime monitor to a critical control loop.

- Require documented reasons for any manual overrides.

- Start logging sensor and command streams centrally and protect those logs.

Closing thoughts

You’ll find that designing for control is less about controlling machines and more about designing relationships — between humans and machines, between software and hardware, and between intention and outcome. If you treat control as something negotiated, documented, and testable, you’ll build systems that behave with the modesty and predictability you’d want in any craftsperson. You might never write poetry about a welder, but you’ll sleep better knowing it won’t improvise during the night shift.

Your next actions (short list)

- Pick one machine or line and run a hazard analysis this week.

- Implement one redundancy or simple monitor by next month.

- Hold a one-hour HMI review with operators and take action on their top three frustrations.

You’re building systems that carry momentum and weight. Design for control with curiosity, skepticism, and a generous dose of humility — and you’ll keep both your people and your products intact.