Have you ever stared at a spindle spec sheet and felt like you were reading the horoscope for an appliance you still don’t trust?

2026 Spindle Technology: Torque Curves, RPM Behavior, And Real-World Cutting Power

You’re going to get a friendly, slightly snarky tour through the state of spindle technology in 2026. This guide will help you read torque curves like they’re not trying to trick you, translate RPM behavior into real cutting expectations, and choose or tune a spindle so it behaves like it was engineered for your job — not someone else’s fantasy about light-as-air aluminum parts.

What’s different about spindles in 2026?

You’ve probably noticed a trend: spindles are getting smaller, smarter, and hotter (figuratively and literally). Advances in power electronics, permanent magnet motors, and embedded sensing have raised power density while letting manufacturers squeeze more continuous torque into compact housings. You get better control, more telemetry, and more warnings about impending failure — often before the spindle has ruined your morning.

A few concrete changes you’ll see:

- Widespread use of SiC (silicon carbide) in inverters for higher switching frequency and efficiency.

- Higher adoption of permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) with optimized flux for extended torque range.

- Onboard sensors (vibration, temperature, torque) and local edge processing for predictive maintenance.

- Improved cooling options: liquid cooling for stators, dedicated oil systems for bearings, and hybrid air/liquid designs.

- Increased use of field-weakening strategies for higher top-end RPM while retaining lower-RPM torque control.

The basics: torque, RPM, and power — what you need to remember

You don’t need to be a mathematician to make sense of spindles, but a few formulas will get you a long way:

- Angular velocity: ω = 2π × RPM / 60 (rad/s)

- Mechanical power: P (W) = Torque (N·m) × ω (rad/s)

- Rearranged for torque: Torque (N·m) = P (W) / ω (rad/s)

So when a spec sheet gives you 20 kW at 12,000 RPM, you can work backward:

- ω = 2π × 12,000 / 60 = 1,256.64 rad/s

- Torque = 20,000 W / 1,256.64 = 15.9 N·m

You’ll often see continuous power and peak power. Continuous power is what the spindle can sustain without overheating or damaging bearings. Peak power (or peak torque) is a short-duration capability for tough cuts — useful, but fleeting.

Torque vs RPM curves — the categories that matter to you

Manufacturers present torque curves to show how torque changes with RPM. There are three practical categories you’ll encounter:

- Constant torque region: Torque stays roughly the same as RPM increases (typical for many motor-driven spindles at low RPM).

- Constant power region (torque falls as RPM rises): Above a certain speed, power stays roughly constant while torque drops off with RPM (typical for many high-speed spindles and motors in field-weakening).

- Hybrid or multi-slope curves: A deliberate shape that maximizes usability across a wide RPM range.

You want to understand whether the spindle gives you torque where you need it — at the cut speeds and feeds you actually run.

Example torque curve behaviors

Below is a simplified table showing how three typical spindle types behave across RPM:

| RPM | Belt-drive (low torque at high RPM) | Direct-drive induction (broad midrange) | Direct-drive PMSM with field-weakening (high top-end speed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | High torque (12 N·m) | High torque (18 N·m) | High torque (22 N·m) |

| 2,000 | Moderate torque (9 N·m) | Moderate-high torque (16 N·m) | Moderate-high torque (18 N·m) |

| 6,000 | Low torque (4 N·m) | Moderate torque (12 N·m) | Moderate torque (12 N·m) |

| 12,000 | Very low torque (1.5 N·m) | Low torque (6 N·m) | Lower torque but still useful (8 N·m) |

| 18,000 | Near zero torque (0.5 N·m) | Minimal torque (3 N·m) | Reduced but managed (5 N·m) |

This table is illustrative, not universal. Your spindle’s curve will depend on motor type, cooling, electronics, and mechanical design. But it gives you a feel for how torque tends to be concentrated at lower speeds for some types and better preserved at higher speeds for others.

How to read a torque curve — practical steps

You’re holding a torque vs RPM plot. Here’s how to read it usefully:

- Identify the continuous torque line — this is your daily driver. Don’t assume peaks are sustainable.

- Find the peak torque and note the duration allowed by the manufacturer (seconds, minutes).

- Look for the “knee” where the curve changes from constant torque to constant power — that’s your transition zone.

- Check the gearbox or toolholder data if the spindle is intended to work through gear reduction. Torque behavior after gearing can be different due to inertia and thermal limits.

When you need to set feeds and speeds, base decisions on continuous torque at the RPM of interest, with a safety factor.

RPM behavior and control strategies — what keeps the spindle behaving

You want predictable RPM behavior. Modern spindles use sophisticated control strategies:

- Vector control (FOC — Field Oriented Control): You get tight torque and speed control across a wide RPM range. That means what you command is what you get, as long as you didn’t exceed limits.

- Field-weakening: Allows higher RPM beyond the base speed by reducing effective field, trading torque for speed. This is how PMSMs achieve high top speeds.

- Sensorless control vs encoder-based: Sensorless saves cost but can be unreliable at very low speeds; encoder-based systems give better low-speed torque control and stability.

- Torque ripple compensation: Important for smoothness, especially when you’re doing high-precision work where small torque fluctuations cause tool marks.

If you’ve ever watched a spindle try to hold speed during a rough cut, you know how important good control strategies are. Poor control = speed sag = inconsistent surface finish.

Translating spindle specs into real-world cutting power

You know the spindle torque and RPM. Now you need to know if it’ll cut the material and chip thickness you want. Use these steps:

- Calculate the spindle angular velocity: ω = 2π × RPM / 60

- Compute available mechanical power: P = Torque × ω

- Estimate cutting power needed: P_cut = cutting force × cutting speed (linear, not RPM) / efficiency factor

- Ensure P_cut ≤ P_available × safety factor (typically 0.6–0.8 for continuous cuts, more conservative for interrupted cuts)

Cutting power formulas are job-specific, but here are useful approximations.

Quick conversion table for RPM to angular velocity and torque-to-power

| RPM | ω (rad/s) | 10 N·m -> Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|

| 500 | 52.36 | 0.524 |

| 1,000 | 104.72 | 1.047 |

| 3,000 | 314.16 | 3.142 |

| 6,000 | 628.32 | 6.283 |

| 12,000 | 1,256.64 | 12.566 |

This shows that at high RPM, even modest torque creates substantial power. That’s why high-speed spindles often advertise high kW numbers even though torque seems low.

Example cutting power calculation for a turning/milling operation

You’re milling 6061 aluminum. You want a cut with:

- Cutting width (ae) = 10 mm

- Cutting depth (ap) = 3 mm

- Feed per tooth (fz) = 0.1 mm

- Tool diameter = 20 mm

- Number of teeth = 4

- Cutting speed (Vc) = 200 m/min

First, compute spindle RPM:

- RPM = Vc × 1000 / (π × D) = 200 × 1000 / (π × 20) ≈ 3183 RPM

Feed rate:

- Feed = RPM × z × fz = 3183 × 4 × 0.1 ≈ 1,273 mm/min

The cutting power depends on specific cutting energy (kc). For aluminum 6061, kc might be around 1,500 N/mm² (this varies; use cutting data). Cutting area A = ae × ap = 10 mm × 3 mm = 30 mm². Cutting force Fc ≈ kc × A ≈ 1,500 × 30 = 45,000 N. That number looks huge because specific cutting energy is usually applied per mm² of uncut cross-section at given conditions — but more commonly you’ll get cutting force per width. Real-world practice: use experimentally derived cutting force coefficients or vendor charts. For this example, assume Fc = 450 N (a more plausible milling force for the stated parameters after considering dynamic removal and tool geometry).

Cutting speed in m/s: V = Vc / 60 = 200 / 60 ≈ 3.33 m/s Power P_cut = Fc × V = 450 N × 3.33 m/s ≈ 1,500 W (1.5 kW)

Now check your spindle: at 3,183 RPM, to deliver 1.5 kW requires torque:

- ω = 2π × 3183 / 60 ≈ 333.55 rad/s

- Torque = P / ω = 1,500 / 333.55 ≈ 4.5 N·m

So if your spindle delivers at least 5 N·m continuous torque at ~3,200 RPM, you’re safe. Add margin for tool wear, chip evacuation, and interrupted cuts, so aim for 30–50% higher torque.

Note: The numbers above simplify many complexities — tool geometry, edge radius, spindle-toolholder stiffness, and process damping all change actual cutting forces.

Typical cutting power needs for materials (ballpark figures)

You need to match spindle capability to material. Below are conservative, illustrative values for medium-duty milling at realistic chip loads. Use them as starting points, not gospel.

| Material | Approx. cutting power per mm² of uncut area (kW/mm²) | Typical example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum alloys | 0.02–0.1 kW/mm² | Soft 6061, light milling | Low energy, high speed |

| Mild steel (A36) | 0.1–0.3 kW/mm² | General machining | Widely varying depending on hardness |

| Tool steel / hardened steel | 0.3–0.8 kW/mm² | Tough alloys | Requires heavy-duty spindle |

| Titanium alloys (Ti-6Al-4V) | 0.6–1.5 kW/mm² | Aerospace cuts | Very demanding — needs torque and rigidity |

| Inconel / superalloys | 0.8–2.0 kW/mm² | High-temp alloys | High power and thermal stiffness required |

If you’re machining titanium or Inconel, you learn to respect the spindle the way you respect a two-ton mastiff with a PhD in biting.

Practical selection guide — match spindle to your job

You’ll be tempted by impressive max RPM numbers. Instead, do this:

- Define typical operations: Are you roughing steels, high-speed aluminum, or finishing composites?

- Compute required torque at working RPM for a representative cut (as above).

- Choose a spindle whose continuous torque at that RPM meets or exceeds required torque × safety factor (1.3–1.6).

- Check peak torque for interrupted cuts or tool break-ins; ensure duty cycle matches.

- Consider toolholding, bearing life, and thermal growth — these often bite you when torque specs look ideal on paper.

If your work is mostly high-feed milling of aluminum, prioritize high RPM and power over raw low-speed torque. If your work is roughing steel or titanium, prioritize consistent low-speed torque and stiffness.

Thermal behavior and why you should care

Spindles heat up. When they heat up, they grow, bearings expand, preload changes, and your tolerances wander.

You’ll see three thermal domains:

- Stator heating (windings): affects electrical properties and insulation.

- Bearing heating: changes preload, affects clearance and life.

- Housing thermal expansion: affects runout and Z-axis reference.

Cooling strategies matter:

- Air-cooled spindles are simpler but have the highest thermal drift.

- Liquid-cooled stators reduce thermal growth and allow higher continuous power.

- Dedicated bearing oil systems and thermal compensation (sensors plus automatic offsets) are increasingly common.

If you run long production cycles, liquid cooling and thermal compensation will make your life easy. If you run short jobs, a well-balanced air-cooled spindle can be enough.

Dynamics, chatter, and stiffness — real-world headaches

Chatter is the thing that turns your nicely machined part into a textured horror show. It’s an interaction of:

- Spindle stiffness (especially toolholder and taper),

- Workpiece rigidity and fixturing,

- Tool geometry and radial immersion,

- Spindle speed (some speeds excite structural modes),

- Controller response and torque ripple.

You’ll mitigate chatter by:

- Increasing stiffness (better toolholder, shorter overhang).

- Adjusting speed to avoid structural resonances (use stability lobe diagrams).

- Using damped toolholders or tuned dampers.

- Tuning feed per tooth and engagement.

Modern spindles with lower torque ripple and finer control reduce some chatter modes, but the primary cure is always mechanical stiffness and proper speed selection.

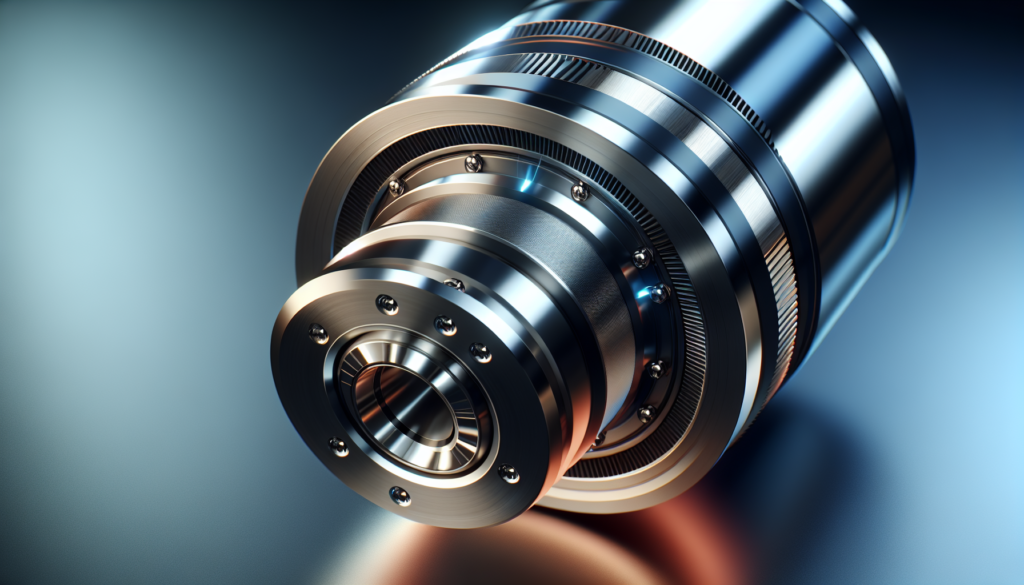

Bearings and toolholding — the unsung heroes

Your spindle’s torque must pass through bearings and into the tool. Bearing type affects both stiffness and allowable speed:

- Angular contact ball bearings: common, cost-effective, good for a mix of loads.

- Ceramic hybrid bearings (ceramic balls, steel raceways): lower friction and higher speed capability with better thermal behavior.

- Full ceramic bearings: higher speed and low thermal drift; expensive and brittle.

- Magnetic bearings: near-frictionless and thermally stable, used in high-end, specialized spindles.

Toolholder systems matter:

- HSK (hollow shank taper) toolholders offer high stiffness and excellent repeatability at high speeds because clamping occurs both axially and radially.

- Shrink-fit holders give superb concentricity and stiffness for high-end finishing.

- Traditional tapered holders (CAT/BT) are fine, but at high RPM and precision work you’ll notice their limits.

If you’re asking for microns of accuracy, you’ll prioritize HSK or shrink-fit and hybrid or ceramic bearings.

Sensors, monitoring, and predictive maintenance

By 2026, you’ll find spindles with embedded sensors that make life less stressful:

- Vibration accelerometers: give you early warning of imbalance, wear, and impending bearing failure.

- Temperature sensors: track stator, bearing, and housing temps.

- Torque sensors or estimators: let you see cutting load and detect tool wear/breakage.

- Acoustic emission sensors: early detection of chip formation anomalies and tool flank wear.

The spindle will tell you it’s unhappy long before it seizes the tool sideways through your workpiece. Use this telemetry to prevent catastrophic failure — and to optimize cut parameters.

Maintenance and operational tips you’ll actually follow

You’ll do better if you adopt a few habits:

- Balance tools and holders to the recommended speed ranges — unbalance is the number-one cause of premature bearing wear.

- Track bearing life and replace before catastrophic failure. Bearing costs are small compared to spindle rebuilds and downtime.

- Keep coolant clean. Contaminated coolant finds its way into bearings, especially in live-tooling and through-tool coolant setups.

- Warm up spindles to operating temperature for precision work. Thermal gradients settle during warm-up.

- Log spindle telemetry and compare trends. A small rise in vibration often predicts a big change a week later.

If you ignore this, you’ll be the person who promises the customer “fresh parts” and then spends two days waiting for a replacement spindle hub to arrive.

How to handle interrupted cuts and heavy rapids

Interrupted cuts (like milling slots or using indexable inserts) spike torque momentarily. To manage:

- Use spindles with good peak torque and short-time duty cycles.

- Ensure toolholders and collets maintain grip under shock. Consider anti-pullout features.

- Use modern drive systems with fast current limits and robust DC bus capacitors to absorb load transients.

- For heavy rapids and load changes, ensure machine control and mechanical brakes are specified to handle the load safely.

Always account for these transients when you specify spindle motor inverters and machine structural capacity.

Field weakening, torque ripple, and top-speed myths

Field weakening is a neat trick: you reduce magnetic field strength so the rotor can go faster without exceeding back-EMF limits. The trade-off: torque falls as RPM rises.

Torque ripple is the oscillation in torque output as the motor rotates. It’s caused by imperfect commutation, cogging torque, and motor design. Torque ripple causes vibration and surface anomalies.

Manufacturers sometimes advertise impressive top-end RPMs that are only possible in field-weakening mode with reduced torque. You’ll want to know the continuous torque at the RPM you’ll be using, not just the max RPM.

Case studies — three real-ish scenarios you might run into

Case 1: High-speed aluminum prototype shop

You’re running light, high-speed finishing cuts on aluminum for cosmetic parts. You want high RPM (12k–24k) and moderate torque. Choose a PMSM spindle optimized for high speed, with liquid-cooled stator and ceramic hybrid bearings. Use shrink-fit holders for concentricity, and balance every tool to >20,000 RPM. Telemetry helps you tune feed per tooth to avoid burrs.

Case 2: Aerospace titanium roughing

You’re hogging Ti-6Al-4V with large radial engagement and heavy axial cuts. You want high continuous torque at low speeds (200–1,200 RPM). Choose a spindle with high low-end torque, robust cooling, and a gearbox or spindle with ample torque reserve. Use rigid toolholding, tune for low chip load per tooth to avoid built-up edge, and monitor torque and temperatures carefully.

Case 3: Mixed job shop with variable tasks

You require flexibility. Choose a spindle with good midrange torque (1,000–6,000 RPM), encoder feedback, and on-spindle sensors. Prioritize toolholders like HSK for fast changeovers while maintaining stiffness. Use the spindle’s telemetry to create process templates for different materials.

Quick tables — conversion and selection cheat-sheets

Torque/Power conversions (useful quick reference)

| Torque (N·m) | RPM | Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 3,000 | 1.57 |

| 10 | 3,000 | 3.14 |

| 10 | 6,000 | 6.28 |

| 15 | 12,000 | 18.85 |

| 20 | 12,000 | 25.13 |

Spindle type comparison (simplified)

| Feature | Air-cooled HDD spindle | Liquid-cooled high-power PMSM | Magnetic-bearing high-speed spindle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max RPM | 12k–18k | 20k–40k | 40k–100k+ |

| Low-end torque | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Thermal stability | Moderate | Excellent | Excellent |

| Cost | Low–Moderate | Moderate–High | High |

| Best for | General purpose shops | High power density jobs | Ultra-high-speed finishing |

Troubleshooting notebook — what to blame when things go wrong

When the surface finish changes: check tool wear, unbalance, spindle torque ripple, or a change in coolant.

When bearings fail early: look for unbalance, contamination, improper preload, or excessive axial loads from offsets.

When RPM sags under load: check drive current limits, DC bus health, and thermal derating. Also consider the spindle is in field-weakening region and cannot sustain torque at that speed.

When chatter appears: check stiffness, tool overhang, spindle health, and try different RPMs — sometimes a 50 RPM change saves a lot of grief.

The future you should expect in the next few years

A few things are likely to be standard rather than fancy in the near future:

- Integrated digital twins and process simulation that predict torque and temperature before you cut a real part.

- More standardization of spindle telemetry outputs (MTConnect, OPC-UA variants).

- Wider adoption of power-dense designs with SiC electronics and integrated cooling solutions.

- Smart toolholders with RFID and dynamic balancing data so your machine knows what you mounted and how it’s balanced.

If you like automation, you’ll enjoy a spindle that tells you what it needs before it refuses to cooperate.

Final checklist for choosing and using a spindle

- Identify your dominant material and typical cut types (rough vs finish).

- Compute the torque required at intended RPM — don’t forget safety margin.

- Check continuous torque at that RPM, not just peak or max RPM numbers.

- Choose bearing/toolholder combos appropriate to your accuracy and speed needs.

- Ensure cooling and thermal compensation match your duty cycle.

- Use telemetry to schedule preventive maintenance — it’s cheaper than surprises.

- Balance tools, keep coolant clean, and monitor trends rather than reacting to loud noises.

You’ll do fine if you treat spindle selection like matchmaking: you want someone who fits your daily habits, not the one who makes the weirdest promises at parties.

Closing thought

You’ll find spindles are secretly temperamental, like a high-performing car that demands premium fuel and a bit of daily attention. If you give them good coolant, balanced tools, meaningful telemetry, and realistic expectations about torque curves and RPM, they’ll reward you with consistent cuts and fewer surprises. If you treat specs as a bedtime story, you’ll get a nightmare in the middle of finishing.